Hydrocephalus: causes, types and treatments

A disorder in which excess cerebrospinal fluid presses on the brain and meninges.

Cerebrospinal fluid is a substance of great importance for the maintenance of the brain. It is a vital element in keeping the nervous tissue afloat, cushioning possible shocks, keeping the brain and meninges intact.The cerebrospinal fluid is a vital element in maintaining the pressure level and electrochemical balance of the nervous system, helping to keep its cells nourished and eliminating the waste generated by its functioning.

With a life cycle that begins with its synthesis in the lateral ventricles and ends with its reabsorption by the Blood system, the cerebrospinal fluid is continuously synthesized, generally maintaining a constant balance between the amount of this liquid substance that is synthesized and that which is absorbed. However, this balance can be altered, causing serious problems due to either excess or insufficient fluid. This is the case of hydrocephalus.

Hydrocephalus: typical symptoms

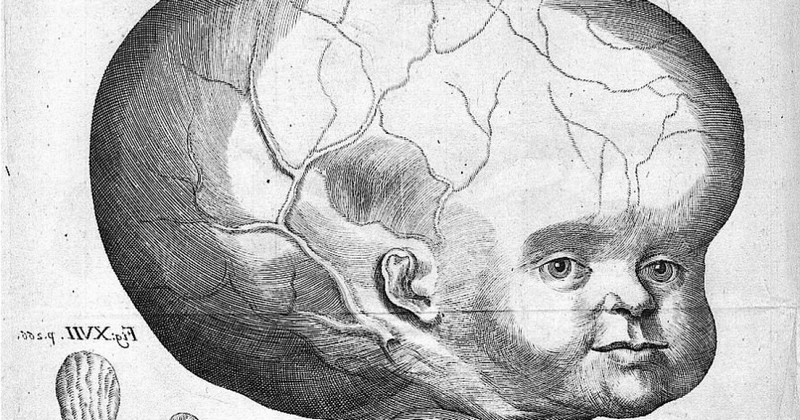

Hydrocephalus is a disorder in which, for various reasons, an excess of cerebrospinal fluid appears, swelling of the cerebral ventricles and/or the subarachnoid space, producing a high level of pressure and producing a high level of pressure in the rest of the brain matter against the skull or between the different brain structures.

Hydrocephalus is a problem that without treatment can be fatal, especially if the areas of the brain stem that regulate vital signs are pressured. The pressure exerted on the different parts of the encephalon will produce a series of symptoms that can vary a series of symptoms that can vary depending on which parts are pressed.. In addition, the age of the subject and tolerance to CSF also affect the appearance of certain symptoms.

However, some of the most frequent symptoms are headaches, nausea and vomiting, double or blurred vision, balance and coordination problems when moving and walking, drowsiness, irritability, slowed growth and intellectual disability if it occurs in the neurodevelopmental period, alterations of consciousness when moving and walking, drowsiness, irritability, slowing of growth and intellectual disability if it occurs in the neurodevelopmental period, alterations of consciousness or changes in personality or memory.

In newborn infants whose skull bones are not yet fully closed, vomiting, convulsions or a tendency to look down are typical. Occasionally, hydrocephalus can also cause macrocephalus, i.e. an exaggerated enlargement of the head in which the meninges and bones are pressed together.

Causes

The causes of excessive cerebrospinal fluid may be multiple, but in general it can be considered to be due to two possible groups of causes. Hydrocephalus usually occurs either when the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid is blocked at some point or when the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid is blocked at some point or when the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid is blocked at some point. at some point, or when the balance the balance between synthesis and absorption of this substance is broken, either because too much is secreted or because it is not reabsorbed.either because too much is secreted or because it is not reabsorbed into the blood.

But these assumptions can be reached in many different ways, whether we are dealing with congenital or acquired hydrocephalus. Some of the causes may be malformations such as spina bifida or that the spinal column does not close before birth (a problem known as myelomeningocele), as well as genetic difficulties.

Throughout the development of life, situations can also occur that end up causing this problem. Cranioencephalic traumas that produce internal hemorrhages (e.g. in the subarachnoid space). (e.g. in the subarachnoid space) may cause a blockage in the flow of fluid. Tumors that pinch or press on the pathways through which the cerebrospinal fluid circulates are another possible cause. Also certain infections, including meningitis, can alter the normal rhythm of the flow of this substance.

Subtypes of hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a problematic medical condition and very dangerous to both life and normative human functioning. This disorder can be congenital, in which it appears as a consequence of situations prior to birth such as malformations, genetic predisposition, trauma or intoxication in the fetal phase, or acquired during birth or at some later time in the life cycle.

The problem itself is in all cases an excess of cerebrospinal fluid which induces different problems due to the pressure caused to the brain, but depending on the cause different types of hydrocephalus can be found.

1. Communicating hydrocephalus

We call communicating hydrocephalus a situation in which there is a blockage after the cerebrospinal fluid has left the ventricles. a blockage occurs after the cerebrospinal fluid exits the ventricles.. In other words, the problem is not in the ventricles, through which the cerebrospinal fluid circulates normally, but is caused by an alteration of the parts of the arachnoid that connect with the blood vessels.

2. Obstructive or non-communicating hydrocephalus

It is called obstructive the type of hydrocephalus in which the problem can be found in that the ventricles or the ducts that connect between them are altered and do not allow a correct flow. This type of hydrocephalus is one of the most commonIt is especially frequent that the reason is to be found in an excessively narrow aqueduct of Sylvius (duct that communicates the third and fourth ventricles).

3. Ex-vacuo hydrocephalus

Ex-vacuo hydrocephalus occurs when for some reason there has been a loss or decrease in brain mass or density. In the face of this loss, generally due to the death of neurons by trauma, hemorrhage or neurodegenerative processes such as dementia, the ventricles have more space available inside the skull, which eventually causes them to dilate (filling with cerebrospinal fluid) until they occupy the available space. It is therefore a type of passive hydrocephaluswhich does not correspond to an alteration of the normal functioning of the cerebrospinal fluid.

4. Normotensive hydrocephalus

A subtype that appears especially in the elderly, this type of hydrocephalus appears to occur as a consequence of poor cerebrospinal fluid reabsorption, in a manner similar to communicating hydrocephalus. However, in this case although the amount of fluid is excessive, the pressure at which it circulates is practically normal (hence its name). (hence its name).

The fact that it usually occurs in the elderly and that the symptoms it causes are similar to those typical of dementia (memory loss, gait problems, urinary incontinence, slowing and loss of cognitive functions) means that it often goes undetected, making it difficult to treat.

Treatments applied in these cases

Rapid action in the case of hydrocephalus is essential if we want to prevent the problem from causing further difficulties. It should be borne in mind that cerebrospinal fluid does not stop secreting, and blockage or dysregulation of the flow can cause the areas in which the fluid is present in excess to swell and cause increasing lesions and collateral damage, given the extensive scope of this type of complication.

Although treating the cause of hydrocephalus is necessary and the treatment of this factor will depend on the cause itself (if it is due to an infection, an inflammatory process or a tumor there will be different ways to treat the case), the first thing to do is to eliminate the excess fluid itself to avoid further damage.

The treatments used in these cases are surgical in natureThe most commonly applied are the following.

Extracranial shunt

One of the most commonly applied treatments in these cases, the extracranial shunt, has a relatively easy to understand operation: it is to remove excess fluid from the cranial cavity and send it to another part of the body where it does not produce alterations, usually one of the cerebral ventricles or the blood system. The basic procedure is to place a catheter between the area from which you want to make the transfer to the area where the flow will be redirected, placing a valve that regulates the drainage is neither insufficient nor excessive.

Although it is the most common and used treatment, it must be taken into account that if the drainage stops working for some reason the problem will reappear, so this resolution may only be temporary. That is why even if this intervention is performed, it is still necessary to investigate the causes that have led to hydrocephalus, and treat them as far as possible. Currently it is less and less used, preferring other treatments.

Endoscopic ventriculostomy of the third ventricle

This intervention is based, like the previous one, on creating a drainage pathway to eliminate excess fluid. However, in this case it is an internal and endogenous an internal and endogenous drainage pathwayThis is done by producing a small opening in the third ventricle to allow excess fluid to flow into the blood (where it would naturally end up). It is usually one of the most successful and reliable types of intervention.

Choroid Plexus Cauterization

If the problem of hydrocephalus is caused by excessive cerebrospinal fluid synthesis or that the fluid is not reabsorbed quickly enough, one treatment option is cauterization or removal of some of the areas that produce it.

In this way, cauterizing some of the choroid plexuses that secrete the cerebrospinal fluid (not all, since the renewal of this one is necessary for the correct functioning of the brain) will reduce the rate at which the flow circulates. It is usually used in conjunction with ventriculostomy. However, it is one of the most invasive forms of intervention.

Bibliographic references:

- Kinsman, S.L.; Johnston, M.V. (2016), Congenital anomalies of the central nervous system. In: Kliegman, R.M.; Stanton, B.F.; St.Geme, J.W.; Schor, N.F. (eds). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier;:chap 591.

- Rosenberg, G.A. (2016). Brain edema and disorders of cerebrospinal fluid circulation. In: Bradley, W.G.; Daroff, R.B.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Jankovic, J. (eds). Bradley: Neurology in Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders; 88.

- Zweckberger, K.; Sakowitz, O.W.; Unterberg, A.W. et al. (2009). Intracranial pressure-volume relationship. Physiology and pathophysiology Anaesthesist. 58:392-7.

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)