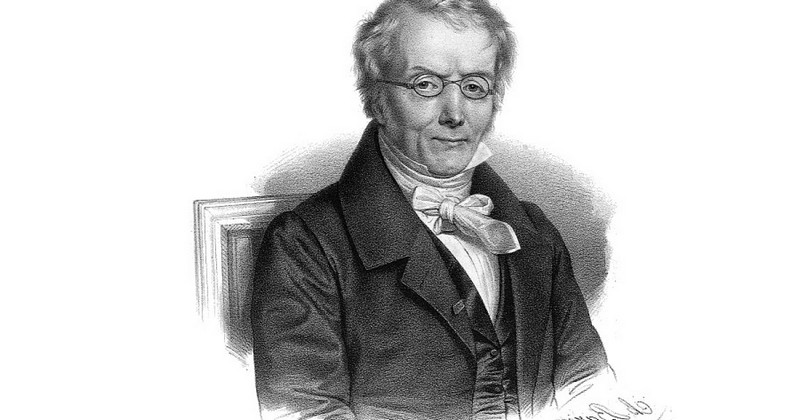

Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol: a biography of this psychiatrist

A summary of the life of this influential French psychiatrist and researcher.

One of the great figures of psychiatry, besides Philippe Pinel, was his disciple Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol.

The figure of this doctor is not limited to the simple fact of being one of the first psychiatrists, but also for having contributed to the systematic study of mental disorders as well as the humanization of those who suffer from them.

We are going to see the figure of such an interesting French alienist physician, the importance of his work and his contributions to the development and recognition of psychiatry as a specialized science through a biography of Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol.

Biography of Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol

Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol was born in Toulouse, France on February 3, 1772, to a large family.to a very large family.

His father worked in an institution where both mentally disturbed patients and delinquents were admitted, without distinction between them. Although this may seem surprising, at that time the idea that delinquency was the product of some kind of insanity was very well established.

Although it was this first approach to mental disorders that would lead Esquirol, years later, to decide to become a psychiatrist, it is true that his beginnings were of a religious vocation. his beginnings were of a religious vocation. In his early years of formation, the young Esquirol would pursue ecclesiastical studies, entering the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Issy.

However, probably inspired by the outbreak of the French Revolution (1789), he abandoned his theological studies to begin a career in medicine in 1792. He studied in several cities, such as Toulouse, Montpellier and Paris, finishing his studies in 1798.

Professional life

In 1899 Esquirol would arrive in Paris and would begin to frequent the service of Jean-Nicolas Corvisart at La Charité and, especially, that of Philippe Pinel at the well-known La Salpêtrière. It would be there that he would establish a very good relationship with Pinel, becoming Esquirol's favorite pupil.

A few years later, in 1805, Esquirol would present his thesis, Les passions considérés comme causes, symptômes et moyen curatifs de l'aliénation mentale. This work brought her some renown, and in 1811 she managed to take charge of the division of mentally ill women at La Salpêtrière.

In 1820, he had the honor of being named a member of the Academy of Medicine, and in 1826, he became a member of the Academy of Medicine. and, in 1826, he became a member of the Council of Public Hygiene and Health of the department of the Seine.

After the death of Pierre-Paul, Royer-Collard would occupy in 1825 the position of chief physician at the Royal Asylum of Charenton, near Paris. Among the patients of this institution came to be the Marquis de Sade himself. Esquirol would exercise his medical direction until the date of his death on December 12, 1840.

Esquirol's contributions to psychiatry

As a disciple and collaborator of Pinel, Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol is known to have followed in his footsteps, both in the more professional aspect of psychiatry and in its more humanitarian sense. Esquirol made several reforming attempts to assist people with mental disorders, seeing them in a more humane way.Esquirol made several reforming attempts to assist people with mental disorders, seeing them in a more humane way and contributing to the separation between people with a mental disorder and people who were delinquent for various non-psychopathological reasons.

One of Esquirol's best known actions would be to send to the Ministry of the Interior the report "Des établissements consacrés aux aliénés en France et de moyens de les améliorer", with the clear intention of making the French state understand the need to help people with mental disorders.

Another of Esquirol's contributions, carried out together with Guillaume Ferrus and Jean-Pierre Falret, would be his participation in the preparatory work for the 1838 Law on Alienated Persons.known for being one of the first legislative texts regulating public psychiatric care.

The figure of Esquirol is also that of a great academic, contributor to the work of the Dictionnaire des sciences médicalesedited by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke. Esquirol would go on to write virtually all psychiatry-related entries, including: Demonomania, Delirium, Insanity, Insanity, Erotomania, Furor, Idiotism, Hallucinations, Suicide, Alienated Houses, Monomania, Mania and Melancholia.

Classification of insanity

It would be within the "Dictionnaire des sciences médicales" work in which Esquirol would present his system on "Madness", classifying it in five great "genres":

1. Lipemania (formerly melancholia).

Lipemania, formerly known as melancholia, would be a delirium about an object or a a delirium about an object or a small number of objects, with a predominant moodwith predominance of sad or depressive mood.

2. Monomania

Monomania would be a delirium limited to a single object or a small group of objects, with joyful and depressive symptomatology.with joyful and expansive symptomatology, as excitement.

3. Mania

Mania would be any delirium that extends to all kinds of objects, with excitement.

4. Dementia

Dementia would imply the deterioration of the capacity to think. A progressive dysfunction of higher functions.

5. Idiocy

Idiocy, also called idiotism or imbecility, refers to the modern idea of intellectual disability. It would be the fact that the person has never presented normal intellectual capacities, below what is expected.

Concept of hallucination

In addition to his system on insanity, it is very noteworthy the nuance that Esquirol gives on the concept of hallucination. Until then, hallucinations were generally considered as diseases of the imagination, not as simple signs or symptoms of an underlying mental disorder.

On more than one occasion the term was even used as a synonym for delirium. Esquirol established the clear distinction between delusions and hallucinationsHe also treated it as a symptom which, although of clinical importance, is not sufficient to diagnose a mental disorder on its own.

Monomania

Finally, Esquirol's great contribution to psychiatry is the formulation of the concept of "monomania". As we have commented before in his classificatory system, this clinical picture is defined as a delirium that is limited to a single object or to a reduced group of them, with excitement and predominance of a joyful or expansive passion.

The patient is obsessed with an idea, presenting an excessively elevated state of mind.. That is to say, it would be equivalent to a manic episode in the current diagnostic systems.

However, what is striking about his concept of monomania is that Esquirol indicates that the person with this psychological problem, outside of the partial delirium that leads to this episode, feels, thinks and acts normally, feels, thinks and acts in a normal way.

This may seem a trifle, but it is thanks to this formulation that allowed the figure of the psychiatrist to be seen as that of a physician highly specialized in psychopathology, being able to identify "the insane who do not seem to be insane", something that a physician with general knowledge would not be able to do.

This was especially important when it came to intervening in courts of justiceThis was especially important when intervening in courts of law, since certain psychopathologies, such as pyromania, kleptomania, and homicidal monomania were a potential danger to society and general practitioners were unable to identify them properly.

His last and great work

The last and great work of Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol was Mental illnesses considered under the medical, hygienic and medico-legal reports in 1838. This work he would publish just two years before his death in 1840 and, in itself, Esquirol himself acknowledged not being as systematic as he would have liked.

This document was in fact an extensive compilation of monographic works published earlier, either independently or as contributions to the "Dictionnaire des sciences médicales". The reason it took him 15 years to write this paper was that, while he did not write as much as he wanted to, he did have an intense professional career, both in insane asylums and in the forensic field, helping to understand the extent to which people deserve dignified treatment, however "deranged" they may be.

Bibliographical references:

- Alvarez A.. JP (2012). Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol. Aliéniste. Rev. Med. Clin. Condes. 23(5): 644-645.

- Huertas, R. (1999). Between doctrine and clinic: the nosography of J.E.D. Esquirol (1772-1840), in Cronos, 2 (1), pp. 47-66.

- Postel, J. and Quetel, C. (1983) Nouvelle Histoire de la Psychiatrie (Toulouse, Privat).

(Updated at Apr 14 / 2024)