Mental rotation: how does our mind manage to rotate objects?

Several researchers have wondered how we are able to have this cognitive ability.

The human mind is a very mysterious thingTherefore, they have tried to discover what are the mechanisms involved behind its functioning. Cognitive psychology has conducted several experiments in which they have tried to elucidate the unknowns behind our thinking.

One of the questions that this branch of psychology has tried to solve has been how we humans manage to process and interpret images that are presented to us inverted or rotated and still see them for what they are. Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler asked this question in 1971, and addressed it experimentally, devising the concept of mental rotation..

Let's see what this idea is all about, and how these researchers delved into it through laboratory experimentation.

- We recommend: "Spatial intelligence: what is it and how can it be improved?"

What is mental rotation?

In 1971, at Stanford University, Shepard and Metzler conducted an experiment that catapulted them to fame in the field of cognitive science. conducted an experiment that catapulted them to fame in the field of cognitive sciences.. In this experiment, participants were presented with pairs of three-dimensional figures with different orientations. The task for the participants was to indicate whether the two figures presented in each trial were identical or whether they were mirror images of each other.

As a result of this experiment, it was seen that there was a positive relationship between the angle at which the figures were presented and the time it took the subjects to answer. The greater the angle at which the images were presented, the more difficult it was for the subjects to indicate whether or not the figures were identical.

Based on these results, it was hypothesized that, when presented with images whose angle is not the one usually shown (90º, 120º, 180º...), what we do mentally is to rotate the figure until we reach a degree of inclination that is "normal" for us, what we do mentally is to rotate the figure until we reach a degree of inclination that is "normal" for us.. Based on this, the more inclination the object has, the longer it will take to mentally rotate it.

Shepard and Metzler, based on all these findings, assumed that the rotation process involved going through a series of steps. First, the mental image of the object in question was created. After that, this object was rotated until it reached the inclination that would allow the subsequent comparison and, finally, it was decided whether or not they were two identical objects or not.

Legacy and further experimentation

Shepard and Metzler, by means of their now famous experiment, initiated the approach to mental rotation experiments investigating different variables. During the 1980s, a new concept emerged from the experimentation of these two researchers, the idea of mental imagery.. This term refers to the ability to mentally manipulate the position of objects, after having made a representation of them in our mind.

Thanks to modern neuroimaging techniques, it has been possible to see how object rotation tasks affect the neuronal level. In the last two decades, using the evoked brain potential technique, it has been possible to record the brain responses of participants while performing this type of task. It has been observed that mental rotation tasks increase the activity of parietal regions, which are involved in spatial positioning.

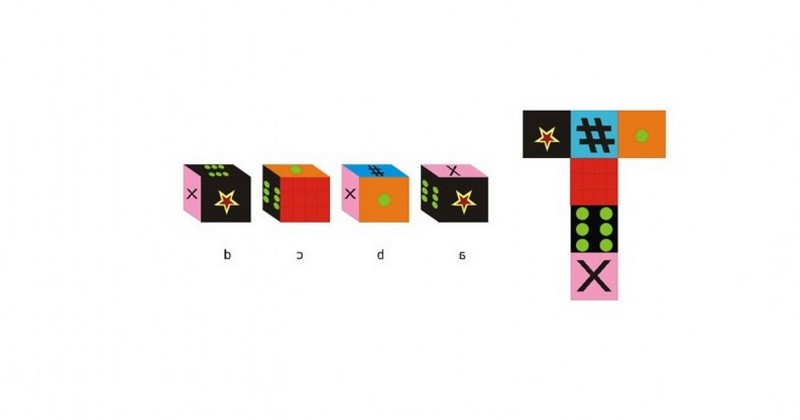

This experiment has been replicated using letters, hands, numbers, and other rotated and inverted symbols to see how much longer subjects took to answer and how knowing the symbol presented influenced the speed at which they answered successfully on trials.

Individual differences

Other research has tried to see if there are relationships between gender, age group, race, or even sexual orientation and how efficiently mental imagery tasks are performed.

In the 1990s, it was investigated whether there were differences between men and women in this type of task, given that better visuospatial performance has traditionally been associated with the male gender. It was observed that if explicit instructions were given on how to perform the mental rotation, men had better scores than women, men had better scores than women in this type of task.However, these differences disappeared if no explicit instructions were given, with both genders performing equally well.

As to whether there were differences depending on the age group, it was found that young people had less difficulty than older people in performing this type of task, it was seen that young people presented fewer difficulties than older people when performing this type of task, as long as it was indicated that there was a time limit.The results showed that young people had less difficulty than older people in performing this type of task, as long as it was indicated that there was a time limit. If there was no time limit, the accuracy of the two age groups did not seem to be very different.

Based on studies conducted over the years, it is known that the presentation of the mirror or identical image also influences the time taken to respond. The time it takes to decide whether the image presented is identical or, on the contrary, a mirror image of the other, is longer when the figure is indeed mirror image.

This is because, first, the person has to rotate it to put it at a proper angle. Then, he has to rotate it in the plane to see whether or not it is a mirror image of the other image presented to him. It is this last step that adds time, as long as the images are not the same.

Criticism of Shepard and Metzler

After conducting their famous experiment, these two researchers received some criticism regarding the results of their experiment..

First of all, some authors of the time asserted that it was not necessarily necessary to resort to mental images to perform this type of task. It must be said that in that decade there was some opposition to the idea that one could resort to mental images, and the idea that thought was, almost without exception, a product of language, was given a great deal of prominence.

Despite this type of criticism, it should be pointed out that in the original experiment the subjects were not told to imagine the figure explicitly, they simply resorted to this strategy on their own.

Other authors asserted that the fact that it took longer to respond to figures with a higher degree of rotation was not necessarily due to this fact, simply that more saccadic movements were made to make sure that they answered correctly..

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)