Müller-Lyer illusion: what is it and why does it occur?

Let's see what this curious optical illusion described by Franz Carl Müller-Lyer consists of.

Optical illusions deceive our visual perception system, making us believe that we see a reality that is not what it seems.

The Müller-Lyer illusion is one of the best known and most studied optical illusions, and has been used by scientists to test numerous hypotheses about the workings of human perception.

In this article we explain what the Müller-Lyer illusion is and which are the main theories that try to explain how it works.

What is the Müller-Lyer illusion?

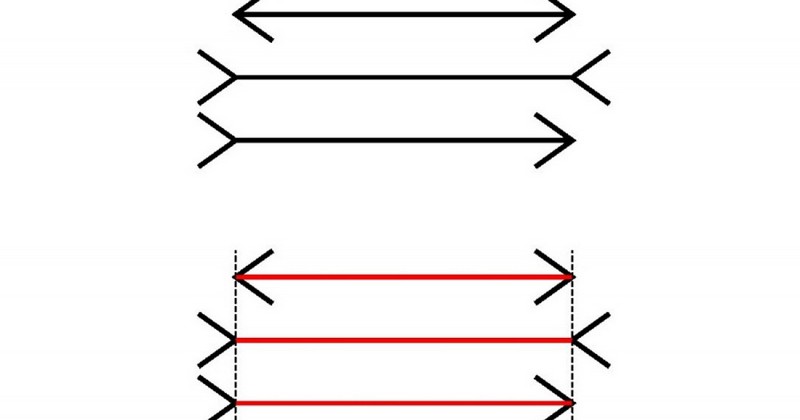

The illusion of Müller-Lyer is one of the best-known geometric optical illusions, consisting of a set of lines consisting of a set of lines ending in arrowheads. The orientation of the tips of each arrow determines how accurately we perceive the length of the lines.

As with most visual and perceptual illusions, the Müller-Lyer illusion has enabled neuroscientists to study the workings of the brain and the visual system, as well as how we perceive and interpret images and visual stimuli.

This optical illusion is named in honor of the German psychiatrist and sociologist, Franz Carl Müller-Lyerwho published up to 15 versions of this illusion in a well-known German magazine at the end of the 19th century.

One of the best known versions is the one consisting of two parallel lines: one of them ends with arrows pointing inward; the other ends with arrows pointing outward. When looking at the two lines, the one containing the inward-pointing arrows is perceived to be significantly longer than the other.

In other alternative versions of the Müller-Lyer illusion, each arrow is placed at the end of a single line, and the observer tends to perceive the midpoint of the lineThe observer tends to perceive the midpoint of the line, just to make sure that the arrows remain constantly on one side of the line.

Explanation of this phenomenon of perception

Although it is not yet known exactly what causes the Müller-Lyer illusion, various authors have provided different theories, the most popular being the perspective theory.

In the three-dimensional world we often tend to use angles to estimate depth and distance.. Our brain is accustomed to perceiving these angles as closer or farther corners, greater or lesser distance; and it also uses this information to make judgments about size.

When perceiving the arrows in the Müller-Lyer illusion, the brain interprets them as distant and near cornersThe brain interprets them as far and near corners, overriding the information from the retina that tells us that both lines are the same length.

This explanation was supported by a study that compared the response to this optical illusion in U.S. children and Zambian children from urban and rural backgrounds. Americans, more exposed to rectangular structures, were more susceptible to the optical illusion, followed by Zambian children from urban areas, and finally Zambian children from rural areas (less exposed to such structures because they live in natural environments).

However, it seems that the Müller-Lyer illusion also persists when the arrows are replaced by circles.which have no relation to perspective or the theory of angles and corners, which seems to call into question the theory of perspective.

Another theory that has tried to explain this perceptual illusion is the theory of saccadic eye movements (rapid movements of the eye when moving to extract visual information), which states that we perceive a longer line because we we need more saccadic movements to see a line with arrows pointing inwardscompared to the line with outward-pointing arrows.

However, this last explanation does not seem to have much foundation, since the illusion seems to persist when there is no saccadic eye movement.

What happens in our brain in optical illusions?

We have known for a long time that our brain does not perceive reality as it is, but tends to interpret it in its own way, filling in the missing gaps and generating hypotheses and patterns to give coherence and meaning to what we see.filling in the missing gaps and generating hypotheses and patterns to give coherence and meaning to what we see. Our brain resorts to cognitive and perceptual shortcuts to save time and resources.

Optical illusions, such as the Müller-Lyer illusion, generate doubts in our perceptual system, and not finding a known and congruent pattern, the brain decides to reinterpret what it sees (in this case, the arrows and lines) through its store of previous experiences and statistics; and after having extracted the available information, it reaches a conclusion: the lines with the arrows facing outward are longer. An erroneous, but coherent conclusion.

On the one hand, from a physiological point of view, optical illusions (the most frequent, ahead of auditory, tactile and gustatory-olfactory illusions) can be explained as a phenomenon of light refraction, as when we put a pencil in a glass of water and it apparently twists.

These illusions can also be explained as a perspective effect, in which the observer is forced to use the the observer is forced to use a certain pre-established point of view, as in the case of anamorphic illusions.This is the case with anamorphosis, deformed drawings that recover their image without deformation when viewed from a certain angle or cylindrical mirror. In a similar way, certain contrasts between colors and shades, in combination with the movement of the eyes, can generate illusions of false sensation of movement.

On the other hand, from the point of view of the psychology of perception (or Gestalt psychology), it has been tried to explain that we perceive the information that reaches us from the outside, not as isolated data, but as packages of different elements in meaningful contexts, according to some rules of interpretative coherence. For example, we tend to group elements that are similar, and we also tend to interpret several elements moving in the same direction as a single element.

In short, what we have learned over the years, thanks to the work of researchers and neuroscientists with optical illusions such as the Müller-Lyer illusion, is to to be wary of what our eyes seeWe are often deceived by our brain, perceiving what is real but does not exist. To paraphrase the French psychologist, Alfred Binet: "Experience and reasoning prove to us that in all perception there is work".

Bibliographical references:

- Bach, M., & Poloschek, C. M. (2006). Optical illusions. Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil, 6(2), 20-21.

- Festinger, L., White, C. W., & Allyn, M. R. (1968). Eye movements and decrement in the Müller-Lyer illusion. Perception & psychophysics, 3(5), 376-382.

- Merleau-Ponty. 2002. Phenomenology of perception . Routledge.

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)