Wason’s selection task: what is it and what does it show about reason?

What is the Wason selection task, and what is it used for in research on rationality?

For millennia it has been considered that human beings are analytical and rational animals, that we can hardly make mistakes when we think about reason.We can hardly make mistakes when we think in a reasoned and deep way about a problem, be it mathematical or logical.

While there may be cultural and educational differences, the truth is that this has come to be assumed as something inherent to the human species, but to what extent is it true?

Peter C. Wason had the good fortune, or misfortune depending on how you look at it, to prove with a very simple task that this was, plain and simple, not entirely true. With a very easy task, called Wason's selection task, this researcher was able to observe how manyThis researcher was able to observe how many of our apparently analytical decisions are not analytical.

Here we will explain what this task consists of, how it is solved and to what extent the context influences its correct resolution.

Wason's selection task: what does it consist of?

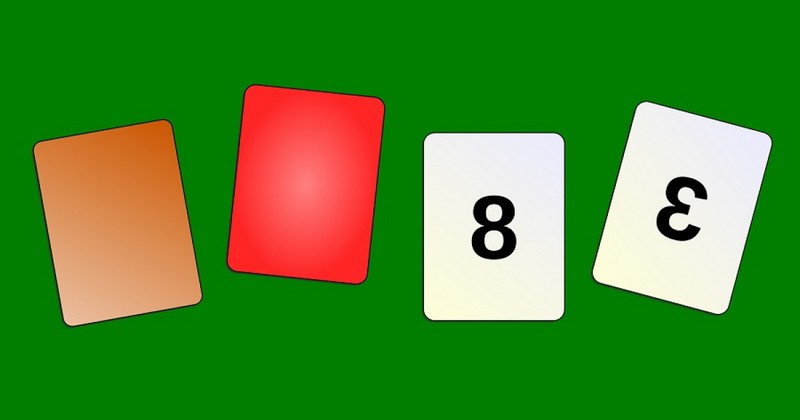

Let's imagine that on a table there are four cards. Each of them has a number on one side and a letter on the other. Let's say that at the moment the cards are laid out in such a way that they look like this:

E D 2 9

We are told that if on one side there is the letter E, on the other side there will be an even number, in this case, 2. Which two cards should we pick up to confirm or disprove this hypothesis?

If your answer is the first and third cards, you are wrong. But don't be discouraged, since only 10% of the people who are presented with this task manage to answer correctly. The correct action was to turn over the first and last cards, since they are the ones that allow us to know if the previous statement is true or not. This is so because when card E is picked up, it is checked if there is an even number on the other side. If this is not the case, the statement would not be correct.

This example given here is the task proposed by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966 and is what is called the Wason Selection Task. It is a logic puzzle in which people's reasoning ability is tested. Human thinking follows a series of steps to reach conclusions. We elaborate a series of approaches whose premises allow us to reach conclusions.

There are two types of reasoning: deductive and inductive. The first is the one that occurs when all the initial information allows reaching the final conclusion, while in the case of inductive reasoning there is concrete information that allows obtaining new information, but in non-absolute terms. In the case of Wason's task, the type of reasoning that is applied is deductive reasoningalso called conditional reasoning. Thus, when solving the task, the following should be taken into account:

Card D should not be picked up because, regardless of whether or not it has an even number on the other side, it does not disprove the statement. That is, we have been told that on the other side of letter E there should be an even number, but we have not been told at any time that any other letter cannot have that same type of number.

The letter with the 2 should not be picked up because if there is an E on the other side it verifies the statement, but it would be redundant since we would have already done it when picking up the first letter. If there is no E on the other side, it does not refute the statement either, since it has not been said that an even number must have the letter E on the other side.

The last side with the 9 should be raised because, in case there is an E on the other side, it refutes the statement, since it means that it is not true that in every card with the letter E there is an even number on the other side.

The matching bias

The fact that most people fail the classic Wason task is due to a matching bias. (matching bias). This bias makes people turn over those cards that only confirm what is said in the statement, without thinking about those that could falsify what is said in it. This is somewhat shocking, given that the task itself is quite simple, but it is displayed in a way that, in case the statement is abstract, makes people fall into the deception discussed above.

This is why Wason's selection task is probably one of the most researched experimental paradigms of all time, since it challenges in a somewhat frustrating way the way we human beings reason. In fact, Wason himself, in a paper published in 1968, stated that the results of his experiment, which we should remember were only 10% correct, were disturbing.

It has been assumed throughout history that the human species is characterized by analytical reasoning, however, this task demonstrates that, in many cases, decisions are made in a completely irrational way..

Context changes everything: content effect

When this test was presented in a decontextualized form, that is, speaking in terms of numbers and letters as is the case here, the research showed very poor results. Most people answered incorrectly. However, if the information is presented with something from real life, the percentages of correct answers change.

This was tested in 1982 by Richard Griggs and James Cox, who reformulated the Wason task as follows.

They asked participants to imagine that they were police officers entering a bar.. Their task was to check which minors were consuming alcohol and thus committing an offense. In the bar there were people drinking, people not drinking alcohol, people under 18 and people over 18. The question participants were asked was which two groups of people should be questioned in order to do the job well and as quickly as possible.

In this case, about 75% answered correctly, saying that the only way to make sure that they were not committing the aforementioned infraction was to ask the group of minors and the group of people who consumed alcoholic beverages.

Another example showing how the context makes one more efficient in answering this task is the one proposed by Asensio, Martín-Cordero, García-Madruga and Recio in 1990, in which, instead of alcoholic beverages, the question was asked to the underage group and the drinking group.in which instead of alcoholic beverages they talked about vehicles. If a person drives a car, then he or she must be over 18 years old. Putting the participants the following four cases:

Car / Bicycle / Person over 18 / Person under 18.

As in the previous case, here it is clear that the letter of the car and the letter of the Person under 18 must be rotated, 90% answered correctly. Although the task in this case is the same, to confirm or falsify a statement, here, as there is contextualized information, it is faster and it is clearer what should be done to answer correctly.

It is here that we speak of the content effect, i.e., the way in which human beings reason not only depends on the structure of the problem, but also on its content, whether or not it is contextualized and, therefore, we can relate it to real-life problems.

The conclusions drawn from these new versions of the Wason task were that, when reasoning, certain mistakes are made. This is because greater attention is paid to superficial featuresespecially those that are limited to confirming the abstract hypothesis. The context and information of the exercise affect the correct resolution of the exercise because comprehension is more important than the syntax of the statement.

Bibliographical references:

- Asensio, M.; Martín Cordero, J.; García-Madruga, J.A. and Recio, J. No Iroqués era mohicano: The influence of content in logical reasoning tasks. Estudios de Psicología, 43-44, 1990, p. 35-60.

- Cox, J. R. and Griggs, R. A. Memory & Cognition (1982) 10: 496.

- Wason, P. C.; Shapiro, D. (1966). "Reasoning." In Foss, B.k M. New horizons in psychology. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Wason, P. C. (1971). "Natural and contrived experience in a reasoning problem". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 23: 63-71.

- Evans, J. St; Lynch, J. S. (1973). "Matching bias in selection task. British Journal of Psychology". Matching bias in selection task. British Journal of Psychology 64: 391-397.

(Updated at Apr 14 / 2024)