History of social psychology: phases of development and main authors.

Summary of the main milestones of this branch of psychology, in relation to its historical context.

Broadly speaking social psychology is concerned with the study of the relationship between the individual and society.. That is, it is interested in explaining and understanding the interaction between individuals and groups, produced in social life.

In turn, social life is understood as a system of interaction, with particular communication mechanisms and processes, where the needs of each other create explicit and implicit norms, as well as meanings and structuring of relationships, behaviors and conflicts (Baró, 1990).

These objects of study can be traced back to the most classical philosophical traditions, since the interest in understanding group dynamics in relation to individual dynamics has been present even before the modern era.

Nevertheless, the history of social psychology is usually told starting from the first empirical worksThe history of social psychology is usually told from the first empirical works, since it is these that allow it to be considered as a discipline with sufficient "scientific validity", in contrast to the "speculative" character of the philosophical traditions.

Having said this, we will now take a look at the history of social psychology, starting with the first works at the end of the 19th century, up to the crisis and the contemporary traditions.

First stage: society as a whole

Social psychology begins its development in the course of the 19th century and is permeated by a fundamental question, which had also permeated the production of knowledge in other social sciences. This question is the following: what is it that keeps us together within a given social order? (Baró, 1990).

Under the influence of the dominant currents in psychology and sociology, fundamentally based in Europe, the answers to this question were found around the idea of a "group mind" that keeps us together beyond individual interests and our differences.

This occurs at the same time as the development of the disciplines themselves, where the works of different authors are representative. In the psychological field, Wilhelm Wundt studied the mental products generated in community and the bonds they produced. For his part, Sigmund Freud argued that the bond is sustained by affective ties and collective identification processes, especially in relation to the same leader.

From sociology, Émile Durkheim spoke of the existence of a collective consciousness (a normative knowledge) that cannot be understood as individual consciousness but as a social fact and a coercive force. For his part, Max Weber suggested that what holds us together is ideology.This is the basis on which interests are converted into values and concrete objectives.

These approaches were based on considering society as a whole, from which it is possible to analyze how individual needs are linked to the needs of the whole.

Second stage: social psychology at the turn of the century

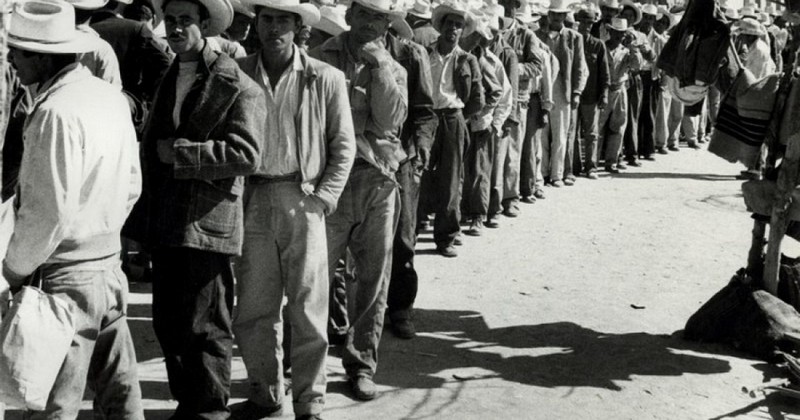

Baró (1990) calls this period, which corresponds to the beginning of the 20th century, "the Americanization of social psychology", insofar as the center of its studies ends up moving from Europe to the United States. In this context, the question is no longer so much what it is that keeps us united in a social order (in the "whole"), but what it is that initially leads us to integrate ourselves into it. In other words, the question is how an individual integrates harmoniously into this social order..

The latter corresponds to two problems of the American context at the time: on the one hand, the growing immigration and the need to integrate people into a given scheme of values and interactions; and on the other hand, the demands of the rise of industrial capitalism.

At the methodological level, the production of data supported by the criteria of modern science, beyond the theoretical production, takes on special relevance here, with which, the experimental approach that had already been developing begins its boom.

The social influence and the individual approach

It was in 1908 when the first works in social psychology appeared. Its authors were two American academics named William McDougall (who placed special emphasis on the psychological) and Edmund A. Ross (whose emphasis was more centered on the social). The former argued that human beings have a series of innate or instinctive a series of innate or instinctive tendencies that psychology can analyze from a social approach.. That is, he argued that psychology could account for how society "moralizes" or "socializes" people.

On the other hand, Ross considered that beyond studying the influence of society on the individual, social psychology should pay attention to the interaction between individuals. In other words, he suggested studying the processes through which we influence each other, as well as differentiating between the different types of influences we exert.

An important connection between psychology and sociology arose at this time. In fact, during the development of symbolic interactionism and the work of George Mead, a tradition often called "Sociological Social Psychology" emerged, which theorized about the use of language in interaction and the meanings of social behavior.

But, perhaps the best remembered of the founders of social psychology is the German Kurt Lewin.. The latter gave a definitive identity to the study of groups, which was decisive for the consolidation of social psychology as a discipline with its own object of study.

Development of the experimental approach

As social psychology consolidated, it was necessary to develop a method of study that, under the positivist canons of modern science, would definitively legitimize this discipline. In this sense, and on a par with "Sociological Social Psychology", a "Psychological Social Psychology" developed, more closely linked to behaviorism, experimentalism and logical positivism..

Hence, one of the most influential works of this time is that of John B. Watson, who considered that for psychology to be scientific, it should be definitively separated from metaphysics and philosophy, as well as adopting the approach and methods of the "hard sciences" (physicochemical).

From this point on, behavior begins to be studied in terms of what it is possible to observe. And it is psychologist Floyd Allport who in the 1920's ended up transferring the Watsonian approach to the practice of social psychology.

In this line, social activity is considered as the result of the sum of individual states and reactions; an issue that ends up moving the focus of study towards the psychology of individuals, especially under the space and controls of the laboratory..

This model, of empicist cut, was mainly focused on the production of data, as well as on achieving general laws under a model of "the social" in terms of pure interaction between organisms studied within a laboratory; which ended up distancing social psychology from the reality it was supposed to study (Íñiguez-Rueda, 2003).

The latter will later be criticized by other approaches of social psychology itself and of other disciplines, which, together with the following political conflicts, will lead the social sciences to an important change in their approach to the social sciences, will lead the social sciences to an important theoretical and methodological crisis..

After World War II

The Second World War and its consequences at the individual, social, political and economic levels brought with it new issues that, among other things, resituated the work of social psychology.

The areas of interest at this time were mainly the study of group phenomena (especially in small groups, as a reflection of large groups), the processes of attitude formation and change, as well as personality development as a reflection and driving force of society (Baró, 1990).

There was also an important concern to understand what lay beneath the apparent unity of groups and social cohesion. On the other hand, there was a growing interest in the study of social norms, attitudes, conflict resolution, and the explanation of phenomena such as altruism. the explanation of phenomena such as altruism, obedience and conformism..

For example, the work of Muzafer and Carolyn Sheriff on conflict and social norm are representative of this period. In the area of attitudes, the studies of Carl Hovland are representative, and in conformity, the experiments of Solomon Asch are classics. In obedience, Stanley Milgram's experiments are classic..

On the other hand, there was a group of psychologists and social theorists who were concerned about to understand what elements had triggered the Nazi regime and the Second World War. and the Second World War. Among others the Frankfurt School and critical theory arose here.whose greatest exponent is Theodore W. Adorno. This opens the way to the next stage in the history of social psychology, marked by disenchantment and skepticism towards the discipline itself.

Third stage: the crisis of social psychology

Not before the previous approaches had disappeared, the decade of the 60's opened new reflections and debates on the what, how and why of social psychology (Íñiguez-Rueda, 2003).

This occurred within the framework of the military and political defeat of the North American vision, which, among other things, made it clear that the social sciences were not alien to social psychology. that the social sciences were not oblivious to historical conflicts and power structures, but rather to conflicts and power structures, but on the contrary (Baró, 1990). Consequently, different ways of validating social psychology emerged, which developed in constant tension and negotiation with traditional approaches of a more positivist and experimentalist nature.

Some characteristics of the crisis

The crisis was not only caused by external factors, which also included protest movements, the "crisis of values", changes in the world production structure and the questioning of the models that dominated the social sciences (Iñiguez-Rueda, 2003).

Internally, the principles that sustained and legitimized traditional social psychology (and the social sciences in general) were strongly questioned. Thus, new ways of seeing and new ways of seeing and doing science, and of producing knowledge.. Among these elements were mainly the imprecise character of social psychology and the tendency to experimental research, which began to be considered as very distant from the social realities it studied.

In the European context key were the works of psychologists such as Serge Moscovici and Henry Tajfeland later the sociologists Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, among many others.

From this point on, reality begins to be seen as a construction. In addition, there is a growing interest in a conflictual approach to social order, and finally, a concern for the political role of social psychology and its transformative potential (Baró, 1990). In contrast to sociological social psychology and psychological social psychology, a critical social psychology emerges in this context.

To give an example and following Iñiguez-Rueda (2003), we will see two approaches that emerged from the contemporary paradigms of social psychology.

The professional approach

In this approach social psychology is also called applied social psychology and may even include community social psychology. can include community social psychology. Broadly speaking, it is the professional inclination towards intervention.

It is not so much a matter of "applying theory" in the social context, but of valuing the theoretical and knowledge production that took place during the intervention itself. It acts especially under the premise of seeking solutions to social problems outside the academic and/or experimental context, and the technologization that had crossed much of social psychology.

Transdisciplinary approach

It is one of the paradigms of critical social psychology, where beyond constituting an interdisciplinary approach, which would imply the connection or collaboration between different disciplines, it is a matter of collaboration without a strict division between one discipline and another..

These disciplines include, for example, psychology, anthropology, linguistics, sociology. In this context, it is of special interest to develop reflective practices and research with a sense of social relevance.

Bibliographical references:

- Baró, M. (1990). Action and ideology. Psicología Social desde Centroamérica. UCA Editores: El Salvador.

- Íñiguez-Rueda, L. (2003). La Psicología Social como Crítica: Continuismo, Estabilidad y Efervescencias. Three Decades after the "Crisis". Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 37(2): 221-238.

- Seidmann, S. (S/A). History of social psychology. Retrieved September 28, 2018. Available at http://www.psi.uba.ar/academica/carrerasdegrado/psicologia/sitios_catedras/obligatorias/035_psicologia_social1/material/descargas/historia_psico_social.pdf.

(Updated at Apr 12 / 2024)