Solomon’s Paradox: Our wisdom is relative.

We are more capable of giving advice to other people than of applying this advice to our own lives.

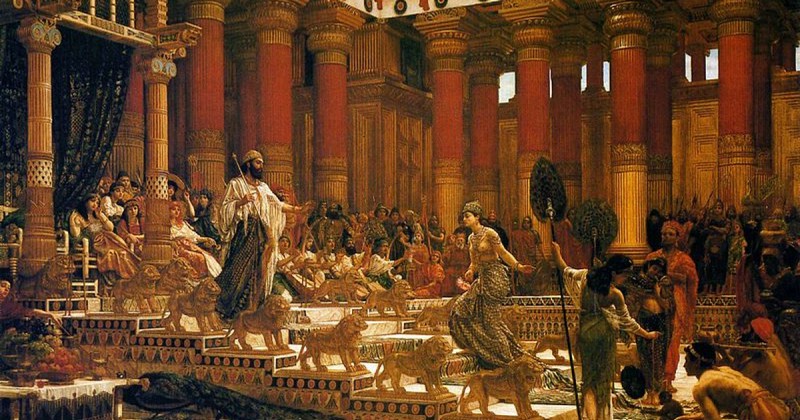

King Solomon is famous for making judgments based on pragmatism. pragmatism and wisdom. In fact, there is a biblical episode in which it is narrated how the good king managed to know the truth in a case in which two mothers dispute over a child, each of them claiming to be the mother of the child. However, the Jewish king proved to be not so skillful in administering the Law of Yahweh to preserve his kingdom.

Solomon ended up letting his own motivations and his greed for great luxuries degrade the kingdom of Israel, which ended up dividing under the reign of his son. This stage blurred the shape of the kingdom, but also served to demonstrate the negative influence that subjective impulses can have on issues that require more rational analysis. It is from this dialectic between objectivity and subjectivity that a cognitive bias is created, called the Solomon's paradox.

Let's see what it consists of.

Solomon is not alone in this

It is difficult to ridicule Solomon for his lack of judgment.. It is normal for us too to have the feeling that we are much better at giving advice than at making good decisions whose outcome affects us. It is as if, the moment a problem comes to affect us, we lose any ability to deal with it rationally. This phenomenon has nothing to do with karmaNor do we have to look for esoteric explanations for it.

It is only an indication that, for our brain, the resolution of problems in which something is at stake for us follows a different logic than the one we apply to problems that we perceive as alien... even if this makes us make worse decisions. This newly discovered bias is known as the Solomon's Paradoxor Solomon's Paradox, in reference to the (nevertheless) wise Jewish king.

Science investigates Solomon's Paradox

Igor Grossman y Ethan Krossfrom the University of Waterloo and the University of Michigan, respectively, have brought Solomon's Paradox to light. These researchers have subjected to experimentation the process by which people are more rational when advising other people than when deciding for us what to do in the problems that occur to us. To do this, they used a sample series of volunteers with steady partners and asked them to imagine one of two possible scenarios.

Some people had to imagine that their partner was unfaithful, while in the case of the other group the person who was unfaithful was the partner of their best friend. Then, both groups had to reflect on the situation and answer a series of questions. reflect on the situation and answer a series of questions related to the situation of the couple related to the situation of the partner affected by the case of infidelity.

It is easier to think rationally about what does not concern us

These questions were designed to measure to what extent the way of thinking of the person consulted was being pragmatic and focused on resolving the conflict in the best possible way. From these results it could be seen that people in the group that had to imagine infidelity on the part of their own partner scored significantly lower than the other group. In short, these people were less able to predict possible outcomes, to take into consideration the point of view of the unfaithful person, to recognize the limits of their own knowledge and to assess the needs of the other person. Similarly, it was confirmed that participants were better at thinking pragmatically when they were not directly involved in the situation.

In addition, Solomon's Paradox was present to the same extent in both young adults (20 to 40 years old) and (20 to 40 years old) and in older adults (60 to 80 years old) (aged 60 to 80 years), which means that this is a very persistent bias that does not correct with age.

However, Grossmann and Kross thought of a way to correct this bias: what if the persons consulted tried to distance themselves psychologically from the problem? Was it possible to think of one's own infidelity as being experienced by a third person? The truth is that it was, at least in an experimental context. People who imagined their partner's infidelity from the perspective of another person were able to provide better answers in the question-and-answer session. This conclusion is the one that can be of most interest to us in our daily lives: to make wiser decisions, it is only necessary to put ourselves in the shoes of a relatively neutral "opinionator"..

The external observer

In short, Grossmann and Kross have shown experimentally that our beliefs about the importance of the "neutral observer" are based on something that exists: a predisposition to act in a less neutral way. predisposition to act less rationally in the face of social issues that are close to our hearts..

Like King Solomon, we are capable of making the best judgments from a role characterized by detachment, but when it is our turn to play our cards, it is easy to lose that rectitude.

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)