The brain’s reward system: what is it and how does it work?

Neuroscientific and psychological clues to understand why we like certain things.

The functioning of the human brain may seem chaotic because of its complexity, but the truth is that everything that happens in it obeys a logic: the brain's reward system.But the truth is that everything that happens in it obeys a logic: the need for survival.

Of course, such an important issue has not been neglected by natural selection, and that is why our nervous system includes many mechanisms that allow us to stay alive: the regulation of body temperature, the integration of visual information, the control of breathing, etc. All these processes are automatic and we cannot voluntarily intervene on them.

But... But what happens when what brings us closer or closer to death has to do with actions learned through experience? In those cases, that are not foreseen by evolution, an element known as the brain's reward system is at work..

What is the reward system?

The reward system is a set of mechanisms carried out by our brain that allows us to associate certain situations with a sensation of pleasure. Thus, based on these learnings, we will tend to try to we will tend to try to make sure that in the future the situations that have generated that experience will occur again..

In a way, the reward system is that which allows us to locate goals in a very primal sense. As human beings are exposed to a great variety of situations for which Biological evolution has not prepared us, these mechanisms reward certain actions over others, making us learn on the fly what is good for us and what is not.

Thus, the reward system is closely linked to basic needs: it will make us feel very rewarded when we find a place that contains water when we have not had a drink for too long, and it will make us feel good when we bond with someone friendly.

Its function is to ensure that whatever we do, and however varied our actions and behavioral choices may be, we always have a compass that consistently points to certain sources of motivation, rather than just anywhere.

Where does the reward circuit pass through?

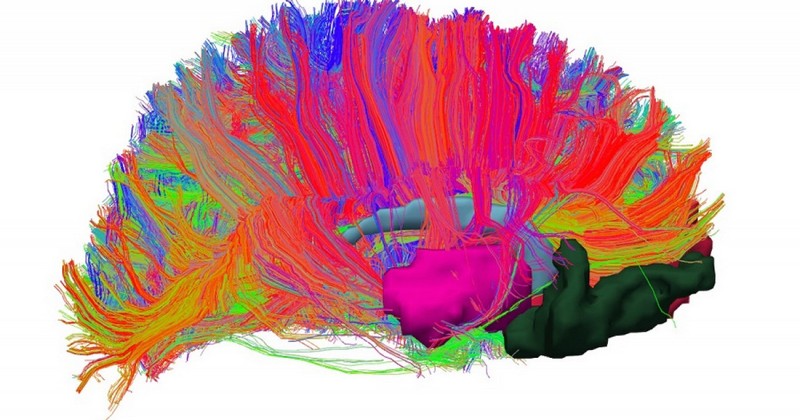

Although everything that happens in our brain happens very fast and receives feedback from many other regions of the nervous system, in order to better understand how the reward system works, its functioning is often simplified by describing it as a circuit with a clear beginning and end: the mesolimbic pathway, characterized among other things by the importance of a neurotransmitter called dopamine.

The beginning of this chain of information transmission is located in an area of the brainstem called the ventral tegmental area. This region is related to the basic survival mechanisms that are automated with the lower part of the brain, and from there go up to the limbic system, a set of structures known to be responsible for the generation of emotions. Specifically, the nucleus accumbens is associated with the emergence of the sensation of pleasure..

This mixture of pleasant emotions and feelings of pleasure passes to the frontal lobe, where the information is integrated in the form of more or less abstract motivations that lead to planning sequences of voluntary actions that bring us closer to the goal.

Thus, the reward circuit starts in one of the most basic and automated places in the brain and moves up to the frontal lobe, which is one of the places most related to learning, flexible behavior and decision making.

The dark side: addictions

The reward system allows us to remain connected to a sense of pragmatism that allows us to survive while being able to choose between various options for action and not having to stick to automatic and stereotyped behaviors determined by our genes (something that happens, for example, in ants and insects in general).

However, this possibility of leaving us a margin of maneuver when it comes to choosing what we are going to do also has a risk called addiction.. Actions that are initially voluntary and totally controlled, such as choosing to try heroin, may become the only option left to us if we become addicted.

In these cases, our reward system will only be activated by consuming a dose, leaving us totally unable to feel satisfaction from anything else.

Of course, there are many types of addictions, and the one that depends on heroin use is one of the most extreme. However, the mechanism underlying all of them is fundamentally the same: the reward center is "hacked" and becomes a tool that guides us to a single goal, making us lose control over what we do.

In the case of substance abuse, certain molecules can interfere directly on the reward circuit, causing it to undergo a transformation in a short time, but addictions can also appear without the use of drugs, simply from excessive repetition of certain behaviors. addictions can also appear without the use of drugs, simply through excessive repetition of certain behaviors.. In these cases, the substances that produce changes in the reward system are neurotransmitters and hormones generated by our own body.

The ambiguities of addiction

The study of the reward system raises the question of where the boundary between addiction and normal behavior lies.. In practice, it is clear that a person who sells all his belongings to sell drugs has a problem, but if we take into account that addictive behaviors can appear without taking anything and that they are produced by the functioning of a brain system that operates in all people constantly, it is not easy to establish the threshold of addiction.

This has led, for example, to speak of love as a kind of relatively benign addiction: the reward system is activated when we relate to certain people and stops responding as much when the person is no longer present, at least for a while. Something similar happens with addiction to cell phones and the Internet: perhaps if we do not take it very seriously it is simply because it is socially accepted.

Bibliographical references:

- Govaert, P.; de Vries, L.S. (2010). An Atlas of Neonatal Brain Sonography: (CDM 182-183). John Wiley & Sons.

- Moore, S.P. (2005). The Definitive Neurological Surgery Board Review. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Parent, A.; Carpenter, M.B. (1995). "Ch. 1". Carpenter's Human Neuroanatomy. Williams & Wilkins.

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)