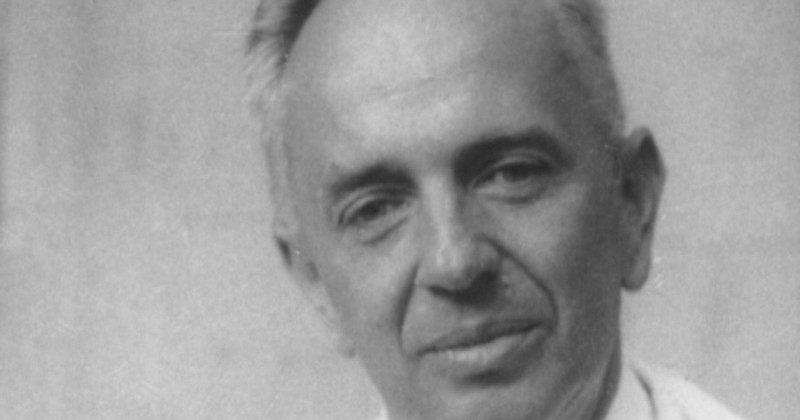

Theodosius Dobzhansky: biography and contributions of this Ukrainian geneticist.

A review of the life of Theodosius Dobzhansky, one of the most important geneticists in history.

Although the 20th century began with the modern theory of Darwinian evolution very widespread, there were many doubts about how natural selection took place. The inheritance of traits was something that had only recently been studied and Mendel's work was still largely unknown in the scientific community.

Genetics was emerging and one of its most famous scholars was Theodosius Dobzhansky, who used it to explain how the evolutionary process took place.

This geneticist of Ukrainian origin is considered one of the most important figures in the study of evolutionary biology and today we are going to discover what happened to his life through a biography of Theodosius Dobzhansky in abridged format.

Short biography of Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Dobzhansky was a Ukrainian-born geneticist and evolutionary biologist whose work is considered fundamental to the field of evolutionary biology. Through his studies he managed to shed some light on the question of how natural selection occurred behind the evolution of species. His 1937 work "Genetics and the Origin of Species" became one of the most outstanding works of research on genetics of all time. He was awarded the U.S. National Medal of Science in 1964 and the Franklin Medal in 1973, among many other awards.

Early years

Theodosius Grygorovych Dobzhansky was born on January 25, 1900 in Nemýriv, a Ukrainian village then part of the Russian Empire. He was the only son of Grigory Dobzhansky, a mathematics professor, and his mother was Sophia Voinarsky. His parents gave him this name because they wanted to have a son but they were a little old and feared they would not be able to have one, so they prayed to St. Theodosius of Chernigov for a son.

In 1910 the Dobzhansky family moved to Kiev, where Theodosius attended high school.. There he spent his youth having as entertainment the collection of butterflies, a hobby that made him want to become a biologist when he grew up. In 1915 he met Victor Luchnik, an entomologist who convinced him to specialize in beetle research.

Youth and university years

Between the years 1917 and 1921 Theodosius Dobzhansky attended the University of Kiev, finishing his studies in 1924, specializing in entomology, i.e. the study of beetles.i.e. the study of insects. He then moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, where he would study under Yuri Filipchenko in a laboratory specializing in the study of Drosophila melanogaster, known as both the vinegar fly and the common fruit fly.

On August 8, 1924 Dobzhansky married geneticist Natalia "Natasha" Sivertzevawho worked with zoologist Ivan Ivanovich Shmalgauzen in Kiev. The couple had a daughter, Sophie, who would go on to marry American archaeologist and anthropologist Michael D. Coe. Before emigrating to the United States, Theodosius Dobzhansky published 35 scientific papers on entomology and genetics.

Relocation to the United States

Theodosius Dobzhansky emigrated to the United States in 1927 on a grant from the Board of International Education of the Rockefeller Foundation. He arrived in New York on December 27 of that year and, almost immediately, joined the Drosophila Genus Research Group at Columbia University, working with geneticists Thomas Hunt Morgan and Alfred Sturtevant. This research group revealed very important information about the cytogenetics of flies, i.e., the hereditary material in these insects.

Added to this, Dobzhansky and his team contributed to the establishment of the Drosophila subobscura as a very suitable animal model for evolutionary biology studies.. Theodosius Dobzhansky's original belief, after studying with Yuri Filipchenko, was that there were serious doubts about how to use data obtained from phenomena occurring in local populations (microevolution) and phenomena occurring on a global scale (macroevolution).

Filipchenko believed that there were only two types of inheritance: Mendelian inheritance, which would explain variation within species, and non-Mendelian inheritance, which would be conceived more in a macroevolutionary sense. Dobzhansky would later consider that Filipchenko had opted for the wrong option.

Theodosius Dobzhansky followed Morgan to the California Institute of Technology (CALTECH) from 1930 to 1940. In 1937 he published one of the most important papers for the modern evolutionary synthesis, the synthesis of evolutionary biology with genetics, entitled "Genetics and the Origin of Species" (Genetics and the Origin of Species). (Genetics and the Origin of Species). In this work, among other things, he defined evolution as "a change in the frequency of an allele within the gene pool".

Obtaining U.S. citizenship

In 1937 he became a full citizen of the United States, which allowed him to become even more relevant in the field of American genetic research.

Theodosius Dobzhansky's work was instrumental in extending the idea that natural selection occurs through mutations in genes.. Perhaps out of envy or competitiveness, it was also at this time that he fell out with Alfred Sturtevant, one of his colleagues in the Drosophila group.

In 1941 Dobzhansky received the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, the same year in which he became a member of the Drosophila group.In 1941 Dobzhansky received the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, the same year he became president of the Genetics Society of America in 1941. In 1943 the University of Sao Paulo awarded him an honorary doctorate. He returned to Columbia University in 1940-1962. He is also known for being one of the signatories in the debate raised by UNESCO in 1950 on The Racial Question.

In 1950 he is awarded the title of president of the Society of American Naturalists, president of the Society for the Study of Evolution in 1951, president of the Society of American Zoologists in 1963, a member of the Board of Directors of the American Eugenics Society in 1964, and president of the American Teilhard de Chardin Association in 1969.

Last years

Theodosius Dobzhansky's wife, Natasha, died of coronary thrombosis on February 22, 1969, a misfortune that joined the one she had already been suffering from since the previous year when she was diagnosed with lymphocytic leukemia.. The prognosis was that he would live a few more months, at most a few years at best.

In 1971 he retired and moved to the University of California, where his student Francisco J. Ayala became an assistant professor and where Dobzhansky continued to serve as professor emeritus. In 1972 he was chosen as the first president of the BGA (Behavior Genetics Association) and was socially recognized for his work on behavioral genetics. and was socially recognized for his work on behavioral genetics and founder of that association, also creating the Dobzhansky Award given to those who have dedicated themselves to the study of this discipline.

Although he was retired, it was in his last years of life it was in the last years of his life that he published one of his most famous essays, "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution", "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution", "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution". ("Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution") and, at that time, he influenced the paleontologist and priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

In 1975 his leukemia worsened, and on November 11 he traveled to San Jacinto, California, for treatment and care. Working until the last moment as a professor of genetics, Theodosius Grygorovych Dobzhansky died of heart failure on December 18, 1975, in Davis, California, at the age of 75. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in the Californian wilderness.

Genetics and the Origin of Species

Theodosius Dobzhansky produced three editions of his most famous book "Genetics and the Origin of Species". Although this book was written for an audience specialized in biology, it was carefully written to make it as understandable as possible. It is considered one of the most important books written throughout the 20th century on evolutionary biology. In each revision of "Genetics and the Origin of Species", Dobzhansky added new contents to update it..

The first edition of the book, published in 1937, sought to highlight the most recent findings in genetics and how they could be applied to the concept of evolution. The book begins by referring to the problem of evolution and how the most modern discoveries in genetics could help to find a solution. The main topics discussed are: the chromosomal basis of Mendelian inheritance, how changes in chromosomes affect more than gene mutations, and how mutations shape specific and racial differences.

The second edition of "Genetics and the Origin of Species" came in 1941, and in it he added even more information explaining, in addition, what scientific findings in the field of genetics he made in the four years between the first and the second. About half of the new research he did in that time was added to the last two chapters of the book: Patterns of Evolution, and Species as Natural Units.

The third revision of the book was published in 1951 and in it Dobzhansky revised all ten chapters of the book. revised all ten chapters of the book due to the many findings he had made throughout the 1940s.. In it he added a new chapter entitled "Adaptive Polymorphism", and in the book he included precise and quantitative evidence about natural selection replicated in the laboratory and seen in nature.

The Race Question

In evolutionary biology, the debate on race between Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ashley Montagu is well known.. The use and validity of the term "race" was debated for a long time, without reaching an agreement on whether it was pertinent to use it in science or not. Montagu was of the opinion that this word was associated with very toxic facts, which was why it was best to eliminate it from science altogether, while Dobzhansky disagreed.

Dobzhansky, on the other hand, was of the opinion that science should not give in to the abuses that could have been made socially of a word, considering that the term "race" could continue to be used if it was adequately defined and not misinterpreted in a political or social key. Montagu and Dobzhansky never reached an agreement and, in fact, Dobzhansky put an acid commentary in 1961 commenting on Montagu's autobiography, which translates as follows:

"The chapter on "Ethnic Group and Race" is, of course, deplorable, but we are going to say that it is good that in a democratic country any opinion, no matter how deplorable, can be published" (Farber 2015 p. 3).

The concept of "race" has been important in many life sciences. Modern synthesis revolutionized the concept of race from being used as a Biological and social label to classify human beings into different groups, attributing physical traits and intellectual abilities, to being used today as a mere description of populations that differ in their gene frequencies. The main reason why science today is reluctant to use the term "race" is because of the great abuses that have been committed throughout its history.

That Dobzhansky was in favor of the term "race" not disappearing from the biological sciences did not mean that he was an advocate of racism. In fact, his research led him to conclude that racial interbreeding did not imply any medical problem, something he observed with his multiple experiments with vinegar flies, crossing several breeds of them.This was observed with his multiple experiments with vinegar flies, crossing several breeds of them. He did observe that if the flies belonged to very different races there was a chance that their offspring would not be fertile, but he did not extrapolate this to the human species.

Many anthropologists, before the UNESCO debate on The Race Question began, were trying to find the traits of each "race" in order to establish clearly what defined each one. Dobzhansky considered that this had no scientific value since he had observed that the variation between individuals of the same population was greater than that between groups. In other words: it would be easier to find a generic human prototype than one of each race, since it was not so clear what made a person belong to one race or another.

His views on genetics, evolution and racial interbreeding generated controversy. He asserted that race had nothing to do with groups but rather with individuals and that, therefore, it is not races that interbreed but individuals. Secondly, that if races do not mix then they will eventually become different species, and that it is therefore necessary for them to mix in order to avoid this. In fact, the present races would be the product of past racial interbreeding, and in Dobzhansky's view there would not exist any race that was pure..

Dobzhansky tried to put an end to the alleged science that asserted that physical traits determined race and that according to this, so did position in society. He believed that it was not possible to identify a true lineage for a human being, that genetic background did not determine how great a person was.

(Updated at Apr 13 / 2024)